Covid is endemic, as are its wounds to our psyche.

The “Great Resignation” will pale compared to the collective cognitive slowdown Covid has caused and will continue to cause at home and at work.

Our companies and capitalist societies are hooked on growth, performance, and productivity. We will need to wean ourselves from them because–if we believe the mental health and insomnia statistics–our collective cognitive operating capacity has shrunk.

This bad news can only be tolerated if we see it as a chance to improve management and fundamentally rethink the extent to which we value human sustainability.

Management in the pandemic joined the ranks of the caring professions — with attendant burnout rates. Already in May 2020, only 9% of Western non-managers expressed an interest in being managers, about 80% of them found the job harder than it was a few years ago, and 60% of them did not want to stay in management.

Managing a depressed and anxious workforce changes the job of the manager from someone:

- in charge of and responsible for what people are doing, and focus instead on how they are doing;

- who always pushes for more efficiency to someone who understands that we might need to slow down and lower expectations for productivity; and,

- who will require deeper knowledge of how humans work, deal with stress, and connect — the basics of brain science.

In spring 2020, managers were thrown into the role of emotional emergency responders without training. Today we know more. So let’s review what we have learned and how we can do better.

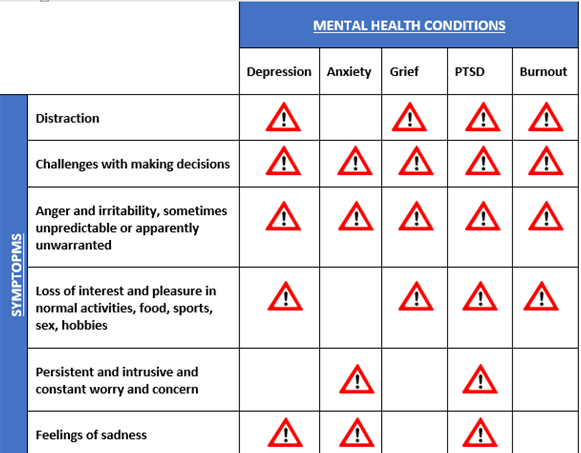

Anxious, distracted, and depressed workers are essentially partially absent at work.

According to 2021 Gallup’s report on the State of the Global Workplace, workers’ daily stress reached a record high, increasing from 38% in 2019 to 43% in 2020 (57% in the U.S. and Canada).

Health conditions, such as depression and anxiety, enable people to come to work or log on but prevent them from working at 100% level. Given that half of US workers are now reporting that they are anxious or depressed, more of us are showing up sick at work. Others are sick or taking care of sick ones, experiencing long Covid and so-called brain fog from the illness or vaccine. Omicron symptoms may be less drastic, but the stress of the illness and caregiving related to it is high. Early in the pandemic, the National Institutes of Health highlighted a study that “revealed very high rates of clinically significant insomnia” along with more acute stress, anxiety and depression.

The result is called presenteeism: the act of coming to work but not being fully productive — staying longer than needed or working while sick. We do so for a whole host of reasons: our inability to perform tasks in the time allotted to them; our concern about letting the team down or fear for our job security; and because of management and peer pressures.

When we do so, we make more mistakes than usual, look exhausted, show up late, and produce lower-quality work. In 2021, about 80% of UK employees reported that there is presenteeism in their workplace.

An increase in substance use, through legalization or as a means to deal with the ache of Covid, does not help. A recent meta-study of cannabis intoxication shows that it leads to small to moderate cognitive impairment (not just when intoxicated) in areas including making decisions, suppressing inappropriate responses, learning through reading and listening, remembering what one reads or hears, and affecting the time needed to complete a mental task.

Also leading to distraction and cognitive impairment is our addiction to the omnipresent cell phone, so heart-breakingly described in this short film, for which its 20-year old Egyptian producer won the award for the best short film at Venice Film Festival.

Measuring presenteeism, of course, is much harder than absenteeism, but some think it costs 10x what absenteeism costs US employers.

What have we learned?

Business schools and business programs did a terrible job of preparing management for Covid. Most business lectures and case discussions still assume that the individuals making decisions are perfectly healthy and in balance — as are those they manage. This has never been a reality. Case studies in particular have tended to portray protagonists as robotic. In fact, our entire school system failed us. We get sex education in school, but no brain education. We take care of our cars, read instruction manuals to coffee machines, but don’t bother to do that for our brains.

Radicalization adds to stress and impairs our ability to think creatively and expansively. In 2021, 40% of Americans identified politics as a significant source of stress, and a small percentage reported contemplating suicide. A recent set of ophthalmology papers suggest that being inside and on screens might have contributed to more kids developing short-sightedness during the pandemic. As kids were becoming physically myopic, adults became cognitively myopic. Myopia narrows perceptions and makes it harder, literally and figuratively, to see the big picture. We focus on what is closest — as in work from home, our family, our neighbors, our communities — and what we recognize. Myopic individuals cannot see into the “distance” such as the implications of their actions.

Self-care seminars and workshops don’t really work — if managers do not change. It does not matter if employees attend mental health workshops unless it’s built into the strategy with the leadership team. There are lots of trainings on recognizing burnout, fewer on not causing it.

Most mental health apps are do not have a scientific basis, and raise significant privacy issues, for companies and employees. Many of the well-being and mental health apps that companies have invested in are collecting data that should worry risk and compliance officers, as well as employees. There are no universal standards for “emotional data.” In addition, the churn is very high — most users stay on for just a few weeks.

The effect of taking time off fades rapidly — if things don’t change at work. For instance, the New York Times reported, a tech company CEO rolled out a policy called “Operation Chillax.” Employees had to take a week off. Other leaders have encouraged people to take vacation postponed by the lockdown of Covid.

The World Health Organization defines burnout as a syndrome “resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed.” It is an ‘occupational’ phenomenon, and not a ‘vacational’ one. Vacation can’t prevent burnout and chronic stressors because those are still there in the workplace,”. If those don’t change, getting away from them is not a solution. Once the break is off, they’ll start back again. It is a vicious workplace circle. Vacation leads to modest decreases in exhaustion and health complaints, which vanish within two to four weeks after resuming work, according to a study published in the Journal of Occupational Health.

Leaves, well-being days, corporate-wide vacation closures, and bereavement leaves are all good. We all need time to heal, care, and mourn those we have lost, including unborn children and dear friends. But some of us don’t need time off and off the shelf, one size fits all, expensive-to-provide benefits.

The next generation of workers — the young people currently suffering from pandemic lockdowns — will be totally different from their predecessors. The pandemic has changed the shape of global happiness. The old have become happier and the young more miserable. Young kids have been robbed of their childhood. K-12 student mental health needs soared with the pandemic. Eating disorders have increased dramatically. The next generation coming into college will suffer from greater levels of anxiety, depression and PTSD. Current college students, even though they are disproportionately vaccinated and not a high-risk group, have been stuck at home. The top thing that millennials and Generation Zers look for in an employer, Gallup reported, was that “the organization cares about employees’ wellbeing.” It is within the top three across the workforce.

What does it meant? Management has become a caring profession and that requires different attitudes and skills.

We will not solve for mental health at work if we don’t focus on the “at work” part — this means rethinking the role of middle managers. They are the pillars of corporate culture and performance and have the most important direct impact on employee well-being. Their emotional state can either help employees flourish at work or the opposite, burn them out.

Investing in training middle managers on the impact of work on mental health and brain functions, and educating them about benefits, is critical to building a culture of well-being and helping employees to overcome mental health challenges at work. Because only if they are trained can they be held accountable for their impact on their teams.

Once they can be held accountable, the company can better appreciate which additional interventions and benefits change employee lives. If not, too much depends on the nature and skill of the individual manager, leaving some employees vulnerable, and leading to poor return in benefit investments. Building a common language and knowledge base around mental health among managers is imperative to being able to measure if and how mental health benefits are working and for whom.

Middle management must be trained on how to manage a cognitively affected workforce (advances in neuroscience and brain health, known approaches to helping people manage trauma and work through grief), understand the legal and compliance framework within which to do so (data privacy, accommodations, and HIPAA), and explore creative activities (such as arts and music) to rebuild social nets, and improve workplace well-being, strengthen belonging, nurture empathy and inclusion, and ignite innovation.

Teach managers to minimize unproductive stress instead of teaching them how to manage it. This can be done via programming. For example, Harvard provides a program to train Mental Health Leadership Champions, taught by faculty from the Harvard School of Public Health, the GlobalMentalHealth@Harvard Initiative and experts from around the world. Or investigate other providers of neuromanagement resources.

But it can also be done by encouraging managers to learn more about brain science. The pandemic opened up a great deal of content in this space, ranging from Stanford neuro-ophthalmologist Andrew Huberman’s show on brain science, sleep, neurotransmitters, and trauma, to psychiatrist and author Daniel Amen’s work on The End of Mental Illness.

Completely rethink the centrality of employee well-being.

In This time it’s personal: Shaping the ‘new possible’ through employee experience, McKinsey suggests that companies develop employee personas (akin to the customer personas that were very popular in the heyday of customer centricity). This will help companies define “moments that matter,” what we described as inflection points in our book on Compassionate Management in the Modern Workplace in a chapter that encouraged management to “Stress About Stressors: What Are Key Inflection Points?”

The personas can be problematic if they become stereotypes. A benefit fund that enables employees to design their support architecture seems to hold greater potential for true customization and better ROI for companies. What an employee needs when will evolve with their experience, what is going on with their loved ones and in their communities.

Think of your team members and colleagues as if they were freelancers. When we contract out work, we think clearly about what is to be done, by whom, under which conditions, and with which tool. We understand that improper specs and unclear instructions will lead to poor outcomes. Companies that use freelance workers gain practice in core tasks that actually lower stress at work according to the World Health Organization: clear tasks at the right skill level that the individual can perform when it suits her/him best at an appropriate remuneration — with the ability to walk away and find a better client if mishandled.

(Re)meet your colleagues, employees, and business partners. Because the pandemic has us out of synch, out of balance and out of sorts, we need to be willing to share who we are now, how we work, and how much pressure we can tolerate. We need to take the time to understand how others have been changed by the pandemic experience, too. What worked for them before may no longer.

To alleviate stress, be more explicit about what can be done and changed (with lots of hard work) and what cannot, so the effort is not wasted. If top leaders communicate what is outside vs within their control, then at least middle managers will feel more supported and appreciated. COVID times call for clear and transparent communication. Being delegated projects with poor visibility adds unnecessary stress to the already heavy workload of middle managers.

Similarly, focus on what is necessary, versus what has always been done. Many US colleges and universities during the pandemic in the US dropped standardized testing requirements — and some will continue doing so. The Los Angeles School district has dropped advanced math requirements because the district claimed it hurt students of color’s potential to do well in school. Similarly, companies have been taking a look at assumptions around job credentials and expectations for promotions. A top finance manager reported that after two colleagues went half-time to avoid burnout, she transformed how the team operates. Explicit growth targets are gone. Deadlines are more flexible. Finally, the work is more project-based, than team-based. “While this enables people to contribute the best they can when they can,” she said, “teamwork and team cohesion suffer.”

Finally, provide safe spaces for resting and thinking. Most of us cannot process information at the speed at which we did before Covid. Distracted workers need longer to regain focus. Getting work done and being asked to present your deep work are two very different activities. Most of the time, there’s only time allocated to the former. Constantly showing that we are productive is exhausting. Weekly updates are better than random “check-ins.”

In 1990, Fortune Magazine headlined the end of the workplace as we know it. We might be there now. There have always been mental health issues are work — we pretended not to see them. Now that they are in the majority, we not only cannot ignore them, but need to change work for all. We will need to slow down and accept the Covid impact — in doing so, we might start building organizations that promote human sustainability.