“A wise man apportions his beliefs to the evidence.”

― David Hume

They say that when we fall in love, we don’t need to explain. They also say that “anyone who falls in love is searching for the missing pieces of themselves.”

We have fallen hard for the term and concept of equity — as in Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) — from the word aequitas or fairness. And also shareholder equity or equity markets. As market equity grew, economic equity fell. Yet, in our rush to atone our sins and redress imbalances, we are not stopping to define words nor, as the pragmatists would wish, to think through what our moral precepts mean in practice.

Although we use language to describe our reality, we learn its meaning and utility from parents, schools, literature, social media, and friends. Sometimes the terms are defined; sometimes, they are not. Rarely are we explicit about the meaning we give them. We accept that we perceive colors differently but assume that we hear words similarly.

Two individuals can describe themselves as sad, but neither will ever know for certain how sadness feels to the other. Instead, they ascribe meaning to the indications of sorrow that they can observe — a look, a gait, an affect. If you tell colleagues, “I am stressed today,” some may interpret this as a plea to be left alone or treated gingerly when it could be a call for help, support, or connection. Often, we take our cues from the interpretations of others, instead of the individual. As we increasingly build bridges across different communities, the costs of assumptions become greater.

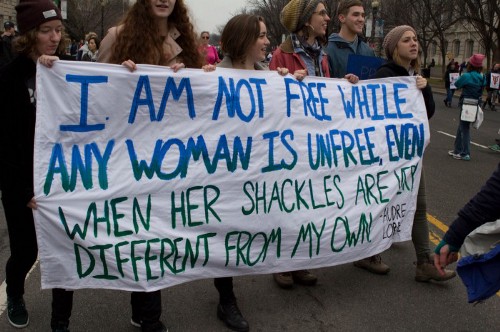

For loaded words such as “racism,” “equity,” and “gender,” we maintain our sense of what concepts such as these mean to us. When asked to explain what we mean by them, we often realize that we don’t know. Many DEI experts don’t have ready definitions, either. It can feel costly for individuals to ask for definitions in business and educational environments — especially when these organizations bandy about slogans.

To ensure that we emerge from the pandemic better able to understand and improve ourselves, each other, and society, we need to define more and assume less. More importantly, how do we derive a common understanding of what they mean in practice?

Equity: From graphics to practice

Versions of this picture became popular last year to help explain the difference between equality and equity, terms whose meanings are often conflated. We find it unhelpful to help us move from the concept to implementation. For example, we can measure how small the kid in the blue shirt is, and we can build the right size stool, so all kids are the same “height.”

The illustration begs a set of questions:

1) How do we do this for immutable, non-visible, non-quantifiable factors? These “stools” might also be financial, human, psychological, and economic support as well as physical.

2) How do we know what the kid in the light blue shirt needs? Do we rely on them to tell us? What if they do not themselves know what they need? Do we then assume what they want?

3) In this scenario, making sure that the kid on the right can have the same experience as the other two does not take anything away from the other two kids. What should we do if we have only two boxes instead of three? To whom do we deny support, and why? And how does that fit with our definition of fairness?

4) How do we guarantee that all these kids be granted their inalienable right to the pursuit of their version of happiness? Would you send your kid to a public school and pay another kid’s tuition to attend a better school?

5) And would you be willing to give up your kid’s stool and prevent them from seeing the game so that another kid might see it? Or would you sue the colleges who didn’t let in your kids?

Soyez réalistes, demandez l’impossible. (“Be realistic, aim for the impossible.”)

The Covid crisis has pushed people worldwide to demonstrate heroic strength while revealing profound weaknesses in our society. Widening gaps in income, wealth, and opportunity in the years before the virus hit left everyone more vulnerable to the disease and its wake. We seem to have rediscovered humans — essential workers, employees, under-represented minorities, children, and adolescents.

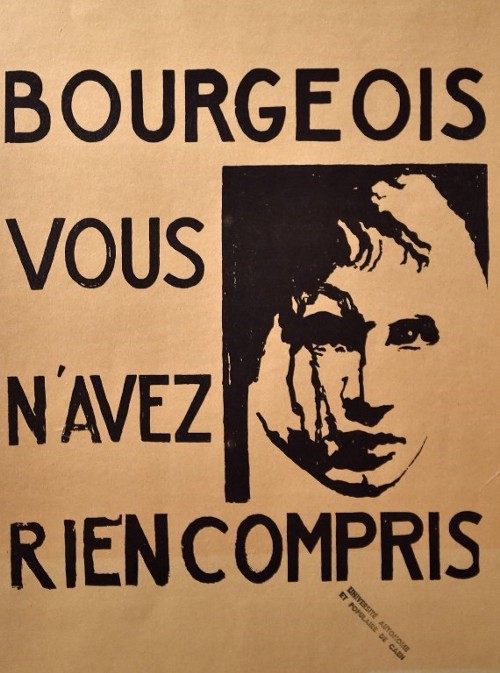

This poster of the May 1968 revolts claimed that the bourgeois class had not understood anything — was clueless. The young protested for more justice, questioned the status quo, blamed their elders and capitalism for the world’s ills; and, workers pushed for better conditions and more rights.

Like 2021, 1968 was a year of both social dislocation and possibility. Companies have made grand promises about being instruments for good and becoming more “human,” creating a more just and equitable world. As we know, words and intentions are important, but how will companies turn these promises into the right actions? Given another chance, will today’s well-intentioned public try to understand and discuss what deep social transformations imply and mean, and not just parrot what they believe is expected of the moment?

Thank you for reading! I would love to hear your reactions and feedback.